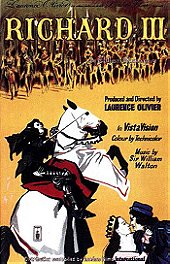

Laurence Olivier directed three Shakespearean adaptations, and having seen two-thirds of them I think I can safely assume that this one is the weakest of the bunch. This version of Richard III is well acted from top to bottom and has nice production values, but there’s no point-of-view. It’s almost as if Olivier grabbed a camera crew, the Royal Shakespearean Company, threw some sets together and yelled “action” on a soundstage.

And the best Shakespearean films do something different or unique with the material. Olivier’s own Hamlet removed the comedic elements, played up the Freudian melodrama and entrapped us in a nightmarish castle of psychosexual drama. That kind of artistic vision is evident in his performance as Richard III, but not in his work as a director. I spent much of the film wishing and wondering what David Lean, Michael Powell or Orson Welles would have done with the material. Olivier does a few long tracking shots as Richard dictates his monologues directly to the audience, but film is a visual medium above all else and sometimes what can better be said with a unique composition is left in as wordiness. Say what you want about Welles’ three adaptations of the Bard’s work, but they don’t lack for daring, vision or offering new perspectives of the material.

But through his tremendous gifts as an actor, Olivier was able to capture your attention in crafting an unforgettable Richard. His shadow looms long over many of the great characters in Shakespeare’s work – we have his iconic Hamlet, after all – and his decision here are quite nice. While in the 1995 version, Ian McKellen plays the part as a scheming spider from the beginning (and if you haven’t seen that version, do so right now), Olivier prefers to play the part as a python slowly tightening his grip over the royal court, strangling his enemies and those who have angered him before they can even realize that they’re in danger.

Part of what makes this villainy and deliciously evil scheming so effective is that Olivier has chosen to outfit his Richard in a ridiculous wig, cartoonish nose and walks with a strange, limping gait. He’s also supposed to be a hunchback, but his tailor must do impressive work because a hump cannot be found. No matter, Olivier’s physicality in the role does half of the work for him. But his nasal tones and clipped speaking voice, a stylistic choice to be certain, roll out of the complicated monologues and make it sound like the most romantic of poetry. When a villain is this charming, it’s hard to entirely hate them no matter how dark or twisted their schemes.

But once we must exit the castle walls and go out into the battlefield a strong problem occurs that no amount of acting can overcome. In the great, vast plains of the battlefield, Olivier’s conservative directing style becomes undone completely. The battle sequences are awkwardly staged and filmed, and Richard feels defeated before he’s even approached the field or uttered out “My horse! My horse! My kingdom for a horse!” His tediously clean direction is clearly trying to rouse itself up for maximum dramatic effect, but it doesn’t come off. When one thinks about the battle scenes that Welles was able to conjure up with limited funds and extras in Chimes at Midnight there is no excuse in the world for why Olivier’s big-budgeted film couldn’t capture the same kind of frenzied magic.

And that’s the problem. Everything was at his disposal to make the definitive Richard III film, but Olivier’s interests were in making a film out of this play in the 40s, roughly right after he had made Henry V and Hamlet. Between then and 1955 Olivier had moved on to Macbeth, the producers agreed to finance that film if he first made Richard III. That’s a much abbreviated version of events, but it’s clear that he had other roles and films in mind and Richard III wasn’t he driving obsession. I think that some of that shows in his work as a director. Hamlet had certain choices made to offer a new perspective on the material, Richard III is just a well-acted, stagey condensed version of the material.

Login

Login